Finally the time came to move into our permanent apartment. Luckily for us, December 1st was a Monday. This meant that the handover inspection from the previous tenant couldn’t occur on the last day of their tenancy, a Sunday, and the handover was done on Friday evening instead. This gave us the whole weekend to move in.

In another fortuitous piece of timing, Mark’s father was in Austria (accompanying Susannah, Mark’s sister, to a ski school in Leogang) at around this time and he was able to come to stay with us beginning a couple of days before the move. Marion’s parents also came down from Ludwigsburg for the weekend. The parental assistance from both sides was very much appreciated.

A complex plan was hatched to move all our belongings from the temporary apartment, clean up there for handover, receive the container from Australia (including such luxuries as our own beds to sleep in) at the new apartment and make sure the twins didn’t get maimed under-foot in the bustle, or otherwise injure themselves in the new environment.

One hiccup came three days before the move when the internet service to our temporary apartment was suspended. It turned out that the previous bill hadn’t been paid on time, and though it was now paid the ISP wasn’t going to reconnect until after we moved out.  Ordinarily this would be a minor nuisance. But with so much to organise around the move, it was a serious handicap. For example, we were using Mobility to rent a van for some of the move and we needed to modify our booking over the internet. We were also planning to use internet banking to pay the bond on the new apartment: if the bond wasn’t paid on time, we would be homeless until it was.

Ordinarily this would be a minor nuisance. But with so much to organise around the move, it was a serious handicap. For example, we were using Mobility to rent a van for some of the move and we needed to modify our booking over the internet. We were also planning to use internet banking to pay the bond on the new apartment: if the bond wasn’t paid on time, we would be homeless until it was.

In Basel, and in many parts of older Europe, furniture can only be brought into the upper levels of many houses directly from the outside, because the stairwells are too narrow. In Amsterdam, the protruding beams on its terrace houses are famous for this purpose. The modern solution is a furniture lift, a clever device that folds out from a trailer to form a telescopic vertical conveyor belt. The removalists erected this against our fifth floor balcony in a matter of minutes, and a stream of boxes began flowing up the lift and into our lounge room, where Mark frantically tried to work out where everything should go.

When you rent an apartment in Switzerland, you are supposed to bring your own lamps. Each room has a hole in the ceiling with two wires protruding from it.  Needless to say, we hadn’t brought our own light fittings with us from Australia, so thankfully Marion’s father had a few spare light bulb sockets which he lent us until we could buy appropriate lamps. Otherwise we would have been stumbling around a dark unfamiliar apartment soon after dusk.

Needless to say, we hadn’t brought our own light fittings with us from Australia, so thankfully Marion’s father had a few spare light bulb sockets which he lent us until we could buy appropriate lamps. Otherwise we would have been stumbling around a dark unfamiliar apartment soon after dusk.

There’s something unnerving about having a pair of exposed wires, potentially carrying 230V, hanging above your head while moving tall items of furniture around. The Swiss light switches, simple toggle buttons from which it is impossible to know whether they are on or off, don’t help. The feeling is exacerbated by having two hyper-stimulated three-year-olds running about opening boxes, potentially finding metal curtain rods. No-one was electrocuted, but it did make for a certain level of, well, high tension.

Although we had been living mostly from suitcases for four months, we had still accumulated a couple of cubic metres of additional clothing, furniture and toys. This, combined with substantially more than one hundred boxes from the container, spilled into the generous space of the new apartment with nowhere to go. In Australia, our house has numerous shelves, cupboards and wardrobes; the new apartment, a modernist style space bounded by sheer white walls and glass sliding doors, has relatively few.  So until we could buy some storage furniture, Mark’s father’s bed in the guest room was literally surrounded by high walls of removalist boxes.

So until we could buy some storage furniture, Mark’s father’s bed in the guest room was literally surrounded by high walls of removalist boxes.

The apartment came with a 5cm thick folder of instructions and rules. Since we weren’t given this until a few days after moving in, we were unaware of the detailed requirements for moving day, such as explicitly instructing the removalists to be careful of the parquetry — yes, this is written in the house rules.

Amongst other regulations are airing your apartment three times per day for fifteen minutes, regularly wet-wiping the parquetry with the cloth provided (indeed, a plastic envelope in the folder contained a soft mesh cloth), cleaning the bathtub only with soap and a soft brush, and washing your section of the cellar at least once per year. The long list of things that are forbidden includes washing pets in the garden, playing music with your windows open, filling or emptying the bathtub after 10pm, shaking out table cloths from the balconies, or hanging up laundry on the balcony facing the Rhine river. At least we now have our own washing machine, even if there are limits on what time of day we can use it. We were also required to order and pay for the engraved steel name plates for our mailbox and doorbell, to be made in the specified font and character size, and fitting the spaces allocated.

It is also forbidden to carry any kind of furniture in the lift, which technically means you have to hire a five-story furniture lift whenever you buy a new bookshelf or armchair.  We unilaterally decided that this rule didn’t apply to still-in-the-box flat-packed furniture, and proceeded to buy almost everything we needed from Ikea. On one trip, Mark and his father packed the Passat wagon so full that there was barely space left to move the gear lever. The Ikea in Pratteln also sports the globally recognisable ball room, which meant at least some of us (pictured at left) were happy to be out furniture shopping.

We unilaterally decided that this rule didn’t apply to still-in-the-box flat-packed furniture, and proceeded to buy almost everything we needed from Ikea. On one trip, Mark and his father packed the Passat wagon so full that there was barely space left to move the gear lever. The Ikea in Pratteln also sports the globally recognisable ball room, which meant at least some of us (pictured at left) were happy to be out furniture shopping.

Friday, February 27, 2009 at 5:10PM

Friday, February 27, 2009 at 5:10PM  It was designed by Paulo Antonio Pisoni, who completed the Cathedral of St. Urs and Viktor in Solothurn after his uncle’s, Gaetano Matteo Pisoni’s, death.

It was designed by Paulo Antonio Pisoni, who completed the Cathedral of St. Urs and Viktor in Solothurn after his uncle’s, Gaetano Matteo Pisoni’s, death.

And one of the Rhine ferries crosses the river near the mill. The ferries are strung from pulleys on a cable over the river, and operate entirely by hydro-power. The ferry pilots simply adjust their rudders so that the flow of water past the boat pushes it across the river. Overall, it was a charming quarter, if a little sedate.

And one of the Rhine ferries crosses the river near the mill. The ferries are strung from pulleys on a cable over the river, and operate entirely by hydro-power. The ferry pilots simply adjust their rudders so that the flow of water past the boat pushes it across the river. Overall, it was a charming quarter, if a little sedate. It took several weeks before we hit upon the correct explanation: dinner guests were moving their chairs on the stone floor of

It took several weeks before we hit upon the correct explanation: dinner guests were moving their chairs on the stone floor of  On the ground floor, the water wheel drives a crude cam that lifts and drops three meter long wooden hammers. The crashing noise dominates the space, as old strips of linen are smashed into a fine pulp, suspended in water. The suspension can then be deposited onto filters by hand, creating a thin layer that dries into paper. Visitors are invited to perform the filtration step, and it turned out that even a three year-old can manage it.

On the ground floor, the water wheel drives a crude cam that lifts and drops three meter long wooden hammers. The crashing noise dominates the space, as old strips of linen are smashed into a fine pulp, suspended in water. The suspension can then be deposited onto filters by hand, creating a thin layer that dries into paper. Visitors are invited to perform the filtration step, and it turned out that even a three year-old can manage it. These kept our would-be tradesmen busy for hours.

These kept our would-be tradesmen busy for hours.  It was installed in 1955, although allegedly it was planned for the 500th anniversary in 1892 of

It was installed in 1955, although allegedly it was planned for the 500th anniversary in 1892 of

Given how eager Wiki and Loxon were to test these, we were forced to surrender ourselves to them as well. But at least we had someone to cling onto in the dark when the terror took hold, even if they were only three years old.

Given how eager Wiki and Loxon were to test these, we were forced to surrender ourselves to them as well. But at least we had someone to cling onto in the dark when the terror took hold, even if they were only three years old. The whole place is such a wonderful change from the artificial, hyper-modern environment of the

The whole place is such a wonderful change from the artificial, hyper-modern environment of the  The

The  But we managed to convince the moving company to let us extract some boxes as they emptied the transport container into a storage one (pictured at right). We would be moving these extra boxes to the new apartment ourselves, so we didn’t want to take too many. But the weather was already turning cold, and we had only summer clothes with us.

But we managed to convince the moving company to let us extract some boxes as they emptied the transport container into a storage one (pictured at right). We would be moving these extra boxes to the new apartment ourselves, so we didn’t want to take too many. But the weather was already turning cold, and we had only summer clothes with us.

This is a model train

This is a model train  It stands beside a kiosk on

It stands beside a kiosk on  as it grew colder still.

as it grew colder still.  Wiki and Loxon were telling us how many times they would ride it long before it was even open.

Wiki and Loxon were telling us how many times they would ride it long before it was even open. Beautifully adorned with painted wooden reliefs, it has turned brass railings, majestic white stallions and garden seats of stained wood swinging on chains. If you look closely at the picture to the right, you’ll see Wiki and Loxon leading a dazed Mark down its staircase.

Beautifully adorned with painted wooden reliefs, it has turned brass railings, majestic white stallions and garden seats of stained wood swinging on chains. If you look closely at the picture to the right, you’ll see Wiki and Loxon leading a dazed Mark down its staircase. Sometimes parenting can be such a trying experience, but one must make sacrifices for the little ones, of course.

Sometimes parenting can be such a trying experience, but one must make sacrifices for the little ones, of course. The figure represents Caritas, the personification of everyday love, which is a fitting subject both for the orphanage in which it was first constructed and for the modern school and childcare which the orphanage has become. It was built by Balthasar Hüglin in 1677, about a decade after the orphanage was established from the medieval monastry.

The figure represents Caritas, the personification of everyday love, which is a fitting subject both for the orphanage in which it was first constructed and for the modern school and childcare which the orphanage has become. It was built by Balthasar Hüglin in 1677, about a decade after the orphanage was established from the medieval monastry. Ordinarily this would be a minor nuisance. But with so much to organise around the move, it was a serious handicap. For example, we were using

Ordinarily this would be a minor nuisance. But with so much to organise around the move, it was a serious handicap. For example, we were using  Needless to say, we hadn’t brought our own light fittings with us from Australia, so thankfully Marion’s father had a few spare light bulb sockets which he lent us until we could buy appropriate lamps. Otherwise we would have been stumbling around a dark unfamiliar apartment soon after dusk.

Needless to say, we hadn’t brought our own light fittings with us from Australia, so thankfully Marion’s father had a few spare light bulb sockets which he lent us until we could buy appropriate lamps. Otherwise we would have been stumbling around a dark unfamiliar apartment soon after dusk. So until we could buy some storage furniture, Mark’s father’s bed in the guest room was literally surrounded by high walls of removalist boxes.

So until we could buy some storage furniture, Mark’s father’s bed in the guest room was literally surrounded by high walls of removalist boxes. We unilaterally decided that this rule didn’t apply to still-in-the-box flat-packed furniture, and proceeded to buy almost everything we needed from Ikea. On one trip, Mark and his father packed

We unilaterally decided that this rule didn’t apply to still-in-the-box flat-packed furniture, and proceeded to buy almost everything we needed from Ikea. On one trip, Mark and his father packed  His works are mostly mechanical devices, using moving parts to generate their impact. Perhaps the most well-known, at least to English speakers, is the

His works are mostly mechanical devices, using moving parts to generate their impact. Perhaps the most well-known, at least to English speakers, is the  Although Santiglaus shares the red suit and gift-giving traits, he comes here on December 6th and is accompanied by a dour assistant called the Schmutzli. In the distant past, the Schmutzli was responsible for punishing those children who had been bad, but after a couple of centuries of failing to find a single bad child, he took over the job of handing out the presents to the good ones. The boys were excited to meet both of these reclusive characters at a special lunch at

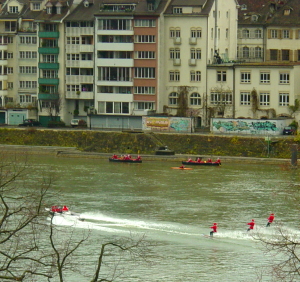

Although Santiglaus shares the red suit and gift-giving traits, he comes here on December 6th and is accompanied by a dour assistant called the Schmutzli. In the distant past, the Schmutzli was responsible for punishing those children who had been bad, but after a couple of centuries of failing to find a single bad child, he took over the job of handing out the presents to the good ones. The boys were excited to meet both of these reclusive characters at a special lunch at  It seems that in Basel at least, having yielded his gift-giving role to the Schmutzli, Santiglaus has found other activities to occupy himself, including canoeing and water-skiing, as we discovered from our windows on the afternoon of December 6th.

It seems that in Basel at least, having yielded his gift-giving role to the Schmutzli, Santiglaus has found other activities to occupy himself, including canoeing and water-skiing, as we discovered from our windows on the afternoon of December 6th. The bridge is also populated with ambulances from the hospital and local car, van and bike traffic. When the wind blows from the South, planes taking off from

The bridge is also populated with ambulances from the hospital and local car, van and bike traffic. When the wind blows from the South, planes taking off from  Seeing it translated into German only enhanced its brand of hyper-novelty, underscoring the incisive theme of information overload. If you get the chance to see it, go.

Seeing it translated into German only enhanced its brand of hyper-novelty, underscoring the incisive theme of information overload. If you get the chance to see it, go.