Our move had been booked for weeks in advance: the removalists would pack all but our most vital furnishings on Monday, and then finish packing and load it all into the container on Tuesday. Alas the Basel utility company, Industrielle Werke Basel decided that this was the perfect week to lay optic fibres under Unterer Rheinweg. And in extremely un-Swiss style, they announced their decision by posting notices on the Sunday afternoon before. With less than 24 hours notice, the south end of the street, where the one-way traffic normally entered, would be blocked. Access would be from the northern end, where a traffic island ordinarily enforced exit only.

the south end of the street, where the one-way traffic normally entered, would be blocked. Access would be from the northern end, where a traffic island ordinarily enforced exit only.

This may have been reasonable, albeit a little confusing, for passenger cars, but container trucks were another matter. Such trucks could have driven through with their wheels straddling the traffic island, if it weren’t for the road sign planted neatly at its centre (shown at right). Evading the signpost however would mean a wheel mounting the kerb. And while this wasn’t against the rules, we were told it wouldn’t be wise with a fully laden container taller than it is wide.

Our astute removalists observed that the sign was fixed to the ground plate with only four standard bolts, and asked some passing police officers if they might be allowed to dismount the sign temporarily. The officers, being good Swiss, assured them that this was against the rules, despite the altered traffic conditions due to roadworks. The removalists then asked if the police might dismount it themselves (they even offered appropriate tools), but this was also deemed against the rules. It seems sign posts have land rights in Switzerland, even when they indicate traffic patterns that have been temporarily suspended.

In the end, the removalists gave up and used a smaller truck to relay our goods to the container in three shifts, which added two hours to the day. Despite this, they still had energy to help us deal with three wooden wardrobes that became the second major hiccup in our move.  We had agreed to take these over from the previous tenants in 2008 after the managing agent assured us we would be able to leave them behind on departure. But when we spoke to the same managing agent about them in 2010, he insisted on the general rental law, under which we were responsible for them unless we could prove otherwise. He seemed not to recall his earlier assurances.

We had agreed to take these over from the previous tenants in 2008 after the managing agent assured us we would be able to leave them behind on departure. But when we spoke to the same managing agent about them in 2010, he insisted on the general rental law, under which we were responsible for them unless we could prove otherwise. He seemed not to recall his earlier assurances.

We had contacted the Heilsarmee (Salvation Army), who run a charity shop that takes and sells old goods, and they had said they would send someone to collect the wardrobes on Monday afternoon. This would be free, unless they were in too poor condition to sell, in which case we could simply pay a fee. The men sent by the Heilsarmee turned up mid-morning, claiming that all their other collections for the day had been cancelled. They then examined the first wardrobe and found a small chip on the edge of the door. No good, they said, these aren’t in perfect condition.

We argued for a while, but they were adamant that these would be impossible to sell. Okay, how much is the fee for removal then? 200 Swiss Francs. What? That’s more than 60 Swiss Francs a piece. No, no, they said, 200 Swiss Francs each, making 600 in total. We could hardly believe our ears, and after much discussion refused to pay such a ridiculous price. It was becoming clear why all their other jobs that day had been cancelled. The men then left, obviously happy that they had finished their work schedule for the day before noon. Thankfully, the removalists had heard the whole exchange and agreed to take the wardrobes away for free.

and after much discussion refused to pay such a ridiculous price. It was becoming clear why all their other jobs that day had been cancelled. The men then left, obviously happy that they had finished their work schedule for the day before noon. Thankfully, the removalists had heard the whole exchange and agreed to take the wardrobes away for free.

Aunt Sabine came on Tuesday to help clean and to take Wiki and Loxon back to Mannheim, freeing us up to concentrate on getting the shipment sent off and then polishing the apartment to Swiss standards. That evening, we took a break from scrubbing to share apéritifs with our newest neighbours, who had recently moved into the adjacent apartment. The man was a genial, elderly Swiss from canton Obwalden at the geographical centre of Switzerland, who served us delicious wine from canton Valais and a fantastic Tête de Moine — a quintessential slice of Switzerland.

The next morning we handed over the apartment keys to the managing agent, who explained that the final bill for shared maintenance wouldn’t be calculated for almost a year. Since we aren’t allowed to retain our Swiss bank accounts, we will be forced to pay this by international wire transfer. As usual, in domestic matters the Swiss seem pathologically incognisant of both the time-value of money and credit risk.

So it was that we embarked on seven weeks of travel. Our first week would be spent staying with Aunt Sabine, Uncle Edgar and Cousin Lea in Mannheim. This was especially felicitous because Lea had the perfect collection of age-appropriate toys and shared them all generously. Aunt Sabine also took us out geo-cacheing (there were several caches within walking distance of their house).

This was especially felicitous because Lea had the perfect collection of age-appropriate toys and shared them all generously. Aunt Sabine also took us out geo-cacheing (there were several caches within walking distance of their house).

We took the opportunity to visit Luisenpark once more, where the wintry weather was helping make the penguins particularly active, and where Wiki and Loxon got in some useful waddling practice, as seen above. Mark also used his Upper Rhine Museum Pass one last time to take Lea, Loxon and Wiki to the Landesmuseum für Technik und Arbeit. While the trio are still a little young to appreciate the physics of the exhibits, there was plenty of excitement to be had spinning wheels, operating pulleys, building bridges and sending up hot air balloons. When the Germans set out to build a technical museum, you can bet the result will be seriously technical.

Monday, October 4, 2010 at 5:08PM

Monday, October 4, 2010 at 5:08PM  Being a contemporary of Leibniz and in constant correspondence with him, Jakob was a significant contributor to the development of calculus, inventing the logarithmic spiral. He also developed the foundations of probability theory, including the Bernoulli distribution and Bernoulli numbers.

Being a contemporary of Leibniz and in constant correspondence with him, Jakob was a significant contributor to the development of calculus, inventing the logarithmic spiral. He also developed the foundations of probability theory, including the Bernoulli distribution and Bernoulli numbers.

This complemented the giant redwood in our back garden, which had suddenly acquired a face (seen above) and a crackling voice. The band of dwarves, elves and faeries that came to celebrate were captivated by the stories and riddles told by the tree. The fact that Uncle Edgar was spotted later with a walkie-talkie was merely a coincidence, of course.

This complemented the giant redwood in our back garden, which had suddenly acquired a face (seen above) and a crackling voice. The band of dwarves, elves and faeries that came to celebrate were captivated by the stories and riddles told by the tree. The fact that Uncle Edgar was spotted later with a walkie-talkie was merely a coincidence, of course. although we had to curb their enthusiasm when it came to throwing large rocks.

although we had to curb their enthusiasm when it came to throwing large rocks. and we’ll set off on seven weeks of travelling on our way back to Australia. For that reason, there’ll be a pause in posts on the Basilisk’s Gaze. But once we are back online in Sydney, we’ll be sure to update you here on the adventures we’ve had en route.

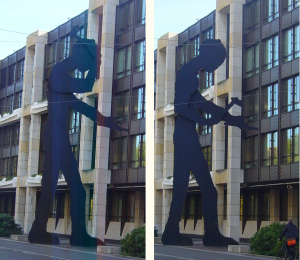

and we’ll set off on seven weeks of travelling on our way back to Australia. For that reason, there’ll be a pause in posts on the Basilisk’s Gaze. But once we are back online in Sydney, we’ll be sure to update you here on the adventures we’ve had en route. This one is 13.5 metres high and 15cm thick. Its arm rises and falls roughly every 15 seconds, pounding out a silent rhythm for the busy traffic below.

This one is 13.5 metres high and 15cm thick. Its arm rises and falls roughly every 15 seconds, pounding out a silent rhythm for the busy traffic below.

We had agreed to take these over from the previous tenants in 2008 after the managing agent assured us we would be able to leave them behind on departure. But when we spoke to the same managing agent about them in 2010, he insisted on the general rental law, under which we were responsible for them unless we could prove otherwise. He seemed not to recall his earlier assurances.

We had agreed to take these over from the previous tenants in 2008 after the managing agent assured us we would be able to leave them behind on departure. But when we spoke to the same managing agent about them in 2010, he insisted on the general rental law, under which we were responsible for them unless we could prove otherwise. He seemed not to recall his earlier assurances. and after much discussion refused to pay such a ridiculous price. It was becoming clear why all their other jobs that day had been cancelled. The men then left, obviously happy that they had finished their work schedule for the day before noon. Thankfully, the removalists had heard the whole exchange and agreed to take the wardrobes away for free.

and after much discussion refused to pay such a ridiculous price. It was becoming clear why all their other jobs that day had been cancelled. The men then left, obviously happy that they had finished their work schedule for the day before noon. Thankfully, the removalists had heard the whole exchange and agreed to take the wardrobes away for free. This was especially felicitous because Lea had the perfect collection of age-appropriate toys and shared them all generously. Aunt Sabine also took us out geo-cacheing (there were

This was especially felicitous because Lea had the perfect collection of age-appropriate toys and shared them all generously. Aunt Sabine also took us out geo-cacheing (there were  Botta, a star Swiss architect, produced the design for a competition in 1986.

Botta, a star Swiss architect, produced the design for a competition in 1986.

It is the origin of everything else in Basel, the city’s growth nourished by the crossing at this vast bend where one of Europe’s largest rivers turns. Upstream it comes from the east, already gathering strength for over 200km. Downstream it flows north, winding another 1000km before emptying into the North Sea. In summer, swimmers submit to its current (Mark — waving — Derya and her boyfriend Robert were among them as you see).

It is the origin of everything else in Basel, the city’s growth nourished by the crossing at this vast bend where one of Europe’s largest rivers turns. Upstream it comes from the east, already gathering strength for over 200km. Downstream it flows north, winding another 1000km before emptying into the North Sea. In summer, swimmers submit to its current (Mark — waving — Derya and her boyfriend Robert were among them as you see).  Karin and Timon hosted us in their fabulous apartment on

Karin and Timon hosted us in their fabulous apartment on  it takes most of a day just to walk around, and hosts over 4500 resident birds — more than any other bird park in the world. Penguins, parakeets, pelicans, pigeons and parrots, of every shape and colour, squawk and stare at you from the exhibits.

it takes most of a day just to walk around, and hosts over 4500 resident birds — more than any other bird park in the world. Penguins, parakeets, pelicans, pigeons and parrots, of every shape and colour, squawk and stare at you from the exhibits. Our principal destination was

Our principal destination was  the fleas thoughtfully left starving for us by our tenants; and Christmas with no furniture. But none of that truly belongs in a travelogue.

the fleas thoughtfully left starving for us by our tenants; and Christmas with no furniture. But none of that truly belongs in a travelogue.